A revolution in flute making took place in the second half of the 17th century. The instrument emerged as the 'baroque flute' with significant modifications including a conical bore, the addition of a key for the right hand little finger, and a more ornate body made in several pieces. It was now fully chromatic (in large part because of the key), but more significantly, it was better suited tonally for a role as a soloist (primarily because of the bore change). The bore change made a big difference in sound—improving the intonation and increasing the volume in the lowest notes, in particular—and incidently allowed the finger holes to be placed higher on the tube, making it slightly easier to handle with small hands than a renaissance flute at the same pitch.

The flute in its new form became popular first in France, where it was well suited for the refined gestures and elegant ornaments of the French baroque style. The early, wide bore French instruments are best played in a significantly lower tessitura than renaissance flutes. They have beautifully expressive and mellow low octaves, and second octaves whose tone, while sweet, can be more penetrating (more soloistic) than that of the renaissance flute.

The photo below show a flute made by by Roderick Cameron in 1982 after instruments stamped "Hotteterre" made in Paris, circa 1700. It is boxwood and ivory with a silver key, and plays at a very low pitch of A=392.

The three piece construction is shown below. The parts are the head (or head joint), the center, and the foot (or foot joint). The six open finger holes are on the center joint. The tenons at either end of the center are wrapped with waxed thread, and they fit snuggly into sockets in the head and foot joints when the flute is put together.

Normally the key was placed somewhat to the player's side of the instrument (as opposed to the audience's side), so as to be more easily reached by the right hand little finger. But the key on the foot joint was always made symmetrical, and the foot could be rotated so that the key was on the other side of the line of holes, and then the instrument could be played left handed, with the right hand above the left.

While baroque flutes were eventually made in several sizes, the most common size by far was the instrument whose low note was d' (the "six-finger note", heard when all six open finger holes were closed). When the holes were opened, one-by-one starting with the sixth hole furthest from the player, a D major scale was the result. Notes outside the D major scale were produced by so-called 'forked fingerings'. An exception is the note D#. This was the original purpose of the single key for the right hand little finger. When the six holes were closed but this key depressed, a hole closest to the end of the flute was opened, and D# sounded. The key was also used in fingerings for a number of other notes.

Starting circa 1720, many flutes were manufactured in four pieces. There were several reasons for this. Three piece flutes were still common in the 1720s, but were not fashionable after 1730 or so.

The photo below shows a mid-18th century flute stamped "LOTZ'. It is a simple design made in boxwood with a brass key. It plays at a pitch of about A=405, but it may have been shortened a bit and may have originally been somewhat lower.

The four piece construction can be seen below. The four pieces may be called the head, the upper center (or simple the center), the lower center (sometimes, the heartpiece), and the foot. The six finger holes are split between the two center joints. We remark that the foot joint and the heartpiece were often kept together in cases, and are often shown together in photos, which can give the false impression that there are only three joints.

The four piece construction eased certain problems of manufacture and maintainance. It was easier to find stable and defect free pieces of wood when shorter pieces are required. And it is easier to get the tapered bore right, and to reream the bore in case of shrinkage, when working with shorter pieces.

But significantly, the four-piece construction also allowed for a corps de rechange. This term means that several interchangeable upper center joints were provided. They allowed the flute to be played at different pitches.

The flute below was made by Folkers & Powell in 1990's. It is a copy of an instrument by Jacob Denner. The original has a corp de rechange consisting of six upper center joints. This one was made with four, at pitches (chosen for the convenience of modern players) A=415, A=400, A=392, and an extra long center a minor third below A=415.

Original baroque and classical flutes were often provided with corp de rechange of from three to seven interchangeable center joints. Usually the difference in length between consecutive joints was about 5mm. This makes a difference of about 5 Hz in the pitch. Note that the interchangable centers of the corp de rechange have tenons and not sockets at their ends. It would be more work to provide sockets on every center.

One-key flutes made after 1720 can be very even and can have excellent intonation. Many (but not all) have a good third octave up to a''', including an f'''.

The sockets and ends of 18th century wooden flutes are often strengthened with rings of ivory, or sometimes of horn. These are called mounts. Ivory flutes might have mounts of silver. They can be elaborate and have a decorative function as well.

When the endcap is removed, the cork that seals the left end of the flute is visible. The position of the cork determines whether the octaves are true. If it is too close to the embouchure, then the octaves are wide; if it is too far, the octaves are narrow. Its correct position depends on the particular flute. Some say 19 mm from the center of the embouchure is best, but the best distance can range from 15 mm to 25 mm. The correct position of the cork will change from center joint to center joint when the flute has a corp de rechange. For a longer center joint, the register, if present, should be pulled out further, but the cork should be moved a bit closer to the embouchure in order to keep the octaves true. The photo below shows the head joint of the Folkers & Powell Denner copy.

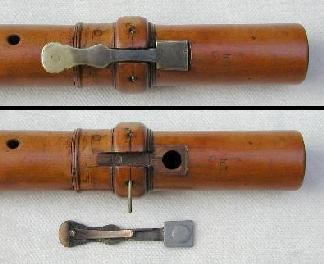

The single key is of silver or brass. The photo below shows how it is held in by a pin (which is partly extracted in the bottom portion of the photo). The spring may be riveted to the key as it is here, or attached to the wood.

Some 18th century flutes were provided with a 'foot register', a simple device that could be used for extending the foot joint by as much as 10 mm. This was useful for tuning the flute—and was especially helpful when the flute had a corp de rechange—but it affects only the D's and some third octave notes. The photo below shows the register closed, partly extended, and pulled out of the foot; the foot belongs to a flute made by Roderick Cameron after originals by C. A. Grenser, circa 1760.

The position of the cork often needs to be adjusted when tuning, and when a center joint from a corp de rechange is changed. Normally this is done by removing the end cap and pushing the cork a bit further into the tube (closer to the embouchure) or further towards the end with a stick or dowel. In general, one moves the cork towards the embouchure, perhaps only a millimeter or less, when pulling the head joint out to flatten the flute, or when using a longer center joint. The exact distance depends on the design of the flute and the amount of change.

To ease the process of moving the cork, some baroque flutes (more near the middle and end of the 18th century than earlier) were equiped with a 'screw-cork'. A threaded wooden or ivory dowel is glued into the cork, and fits into threads cut into part of the end cap. A narrow ivory rod is attached to the dowel and extends through a hole in the endcap; its position indicates where the cork is placed. By turning the end cap, the cork will be pulled out, and rotating the end cap in the other direction (and pushing on the end cap) will push the cork in. The photos below are of the screw-cork assembly on a Grenser copy by Rod Cameron.

The cork is relatively far from the embouchure hole in the photo on the left below, and relatively close in the photo on the right below.

The tuning of a flute is flexible; the pitch of a note can be adjusted by the player to some extent. Good players, no matter what type of flute they may play, will seek to play "in tune". In baroque music, this often this means playing pure intervals with respect to a bass instrument, on notes of any significant length. Nevertheless, we can say that every flute has a basic tuning built into it that the player must work with, or against at times. For the baroque flute, this is not equal temperament.

Throughout much if not all of the 18th century, flutes were theoretically expected to be tuned in a system (a variety of meantone) in which flats were played sharper than sharps. For example, B flat and A sharp were different pitches, with the B flat being sharper (by a comma, about 1/9 of a tone) than the A sharp. J. J. Quantz insists on this in his Essay of 1752 and, like others, gives different fingerings for many of these enharmonic pairs. But Quantz went so far as to claim it beneficial to have two keys on the flute, one for E flat and another for D sharp. This was not generally adopted; only Quantz and two later German makers produced two-keyed instruments of this type; most players would try to effect the difference in tuning with the embouchure when they thought it necessary.

The photo below shows the footjoint of a copy of a Quantz flute by Folkers & Powell. The larger, curved key produces D# when depressed; the shorter, more normal key produces Eb.

The hole under the large D# key is smaller than the hole under the short Eb key.

Quantz advocated a 'tuning head', although not all flutes made under his direction have these. The head joint is made in two pieces, one with a tenon that fits into the main part with the embouchure. The head is made slightly longer by separating the two parts a bit, and then the pitch of the flute is lowered somewhat (but unevenly). My experience is that this tuning head works a bit better than simply separating a normal head and the center, which is the usual method of lowering the average pitch a small amount. The gap in the bore produced when the tuning head is used is less deep than that produced by separating the head and body, and the position of the gap may be less critical for some notes.

Quantz reports, in 1752, that about 30 years prior to his writing, flutes extending to c' had been made by lengthening the foot joint a couple inches and equipping it with a large open standing key covering a hole that produced d'. When all finger holes were closed and the right little finger closed the large key, c' would sound. (There was no c'# on such a flute. This is the same key configuration as on the baroque oboe.)

Quantz relates that the experiment was not a success, that the C-foot ruined the tone and intonation. This may have been true for the first experiments. The bore may need to be changed somewhat if the flute is to still work with the entended foot joint. Later in the 18th century, many excellent flutes were made that had footjoints to c'.

A three piece ivory flute by Jacob Denner, now in the Nuremberg museum, has two footjoints. One is a normal D-foot and one a C-foot with two keys. The flute is thought to date from circa 1720. I am told that it does not play all that well. The flute shown above and just below was made by Rod Cameron. It was inspired by and modeled on the C-foot Denner to a great extent, but Rod used his own experience and talents to modify the design to make it work well.

For a few photographs of Rod making this flute, click here.

At first, the flute was associated primarily with sweet and soft sounds. In a 1702 letter comparing Italian and french music, François Raguenet wrote "...besides all the instruments that are common to us as well as the Italians, we have the hautboys, which by their sounds, equally mellow and piercing, have infinitely the advantage of the violins in all brisk, lively airs, and the flutes, which so many of our great artists have taught to groan after so moving a manner in our moanful airs, and sigh so amorously in those that are tender". That is, oboes were good for lively music; flutes were good for tender music.

Trills on the baroque flute are lively. 18th century fingering charts consistently indicate a preference for trills with wide intervals over narrow ones. This is an important part of its character. (In the 19th century, this would be reversed and narrow, teasing trills would be prefered.) See thoughts on trills.

The tone quality varies mildly from note to note on a one-key flute. Notes like the low G sharp, for example, which must be produced by so-called 'forked' fingerings, have, like hand-stopped notes on a horn, a different quality from the neighboring notes. This is not unpleasant and adds color, rather like the variation in quality of a voice singing different vowels on different pitches.

The soft, veiled sounds of some notes were sometimes exploited by composers, but they were out of place when the composer or the player wanted a more uniform or aggressive tone. Additional keys were fitted to the one-key flute in the second half of the 18th century primarily to alleviate this unevenness, although two were also often added to extend the range downward. Six-keyed flutes appeared in England in the 1750's. Mozart's flute and harp concerto of 1778 was intended for such a flute, but additional keys were not common outside England until the very last years of the 18th century, and even then were far from universally accepted.

One-key flutes were still being made circa 1900 and later; see Catalogs. But these should never be called 'baroque flutes'. Flutes made much after 1750 simply do not have the sound and playing qualities that make a baroque flute what it is.